“…a lover of pictures who lives in a magical society of dreams painted on canvas.” –Charles Baudelaire

Tell us about yourself and what you do as it relates to the history of fashion and dress: Now based in London, I grew up in the depths of rural Shropshire. Having graduated from university with Joint Honours in English and History of Art, I joined Christie’s in early 2004. Thereafter, I worked at Bonhams, before winding up at Sotheby’s Institute of Art in late 2009. I’ve been there ever since, devising and offering an ever-expanding range of public programmes in the fields of art history, contemporary art, the decorative arts, art business and photography. It’s a fascinating – if occasionally exhausting – job which connects me with leading art historians, auction house specialists, gallerists, collectors, journalists and enthusiasts from around the world. It also sees me travel extensively, meeting individuals and groups in Paris, Berlin, Milan, Hong Kong, Los Angeles, Abu Dhabi, New Delhi…

Tell us about yourself and what you do as it relates to the history of fashion and dress: Now based in London, I grew up in the depths of rural Shropshire. Having graduated from university with Joint Honours in English and History of Art, I joined Christie’s in early 2004. Thereafter, I worked at Bonhams, before winding up at Sotheby’s Institute of Art in late 2009. I’ve been there ever since, devising and offering an ever-expanding range of public programmes in the fields of art history, contemporary art, the decorative arts, art business and photography. It’s a fascinating – if occasionally exhausting – job which connects me with leading art historians, auction house specialists, gallerists, collectors, journalists and enthusiasts from around the world. It also sees me travel extensively, meeting individuals and groups in Paris, Berlin, Milan, Hong Kong, Los Angeles, Abu Dhabi, New Delhi…

One strand I’ve taken particular pleasure in developing over the years is that of fashion history. I’ve offered several series of evening lectures in the field: the History of Fashion with Dr Elizabeth Currie in 2011, Art and Fashion with Professor Claire Wilcox, Edwina Ehrman and Oriole Cullen of the V&A in 2013 and The Culture of Fashion with Dr Benjamin Wild (author of A Life in Fashion: The Wardrobe of Cecil Beaton) in 2016. Since 2010, I’ve also offered an annual two-day programme focusing on fine and magnificent jewellery with Daniela Mascetti, International Senior Specialist in Jewellery at Sotheby’s. The overlaps between fashion history and the history of jewellery are often overlooked and Daniela (author of the seminal texts Understanding Jewellery and Celebrating Jewellery: Exceptional Jewels of the 19th and 20th Centuries) is particularly adept at foregrounding these. For example, did you know that there were not one but two intermarriages between the Worth and Cartier families in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries? You can’t fully understand a piece of jewellery without understanding the clothing it was made to be worn with.

One strand I’ve taken particular pleasure in developing over the years is that of fashion history. I’ve offered several series of evening lectures in the field: the History of Fashion with Dr Elizabeth Currie in 2011, Art and Fashion with Professor Claire Wilcox, Edwina Ehrman and Oriole Cullen of the V&A in 2013 and The Culture of Fashion with Dr Benjamin Wild (author of A Life in Fashion: The Wardrobe of Cecil Beaton) in 2016. Since 2010, I’ve also offered an annual two-day programme focusing on fine and magnificent jewellery with Daniela Mascetti, International Senior Specialist in Jewellery at Sotheby’s. The overlaps between fashion history and the history of jewellery are often overlooked and Daniela (author of the seminal texts Understanding Jewellery and Celebrating Jewellery: Exceptional Jewels of the 19th and 20th Centuries) is particularly adept at foregrounding these. For example, did you know that there were not one but two intermarriages between the Worth and Cartier families in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries? You can’t fully understand a piece of jewellery without understanding the clothing it was made to be worn with.

I’m also a regular writer for the British magazine Country Life, reviewing books on art history and social history, as well as contributing the occasional full-length feature.

Why is the study of fashion and dress history important to you? I’m fortunate to be able to draw upon my personal interests in my professional life. For as long as I can remember, I’ve been as much fascinated by the decorative arts (architecture, interiors, gardens, fashion) as by the high arts (painting, sculpture, literature). Complementing both disciplines are my passions for biography and social history: the ways in which humans throughout history have organised their daily lives and relationships. I’ve come to regard the history of dress as the best possible window into the social, political and cultural preoccupations of any given culture, generation or individual. If one knows how to interpret it, clothing can tell us so much about the period or occasion when it was worn, as well as about the men and women who designed and wore it. Besides, the beauty of historical dress – its colours, textures, shapes – is often astounding. I’m just as likely to be excited and inspired – moved, even – by a really beautiful evening gown by Paquin or Mainbocher as I am by a piece of Renaissance sculpture.

Why is the study of fashion and dress history important to you? I’m fortunate to be able to draw upon my personal interests in my professional life. For as long as I can remember, I’ve been as much fascinated by the decorative arts (architecture, interiors, gardens, fashion) as by the high arts (painting, sculpture, literature). Complementing both disciplines are my passions for biography and social history: the ways in which humans throughout history have organised their daily lives and relationships. I’ve come to regard the history of dress as the best possible window into the social, political and cultural preoccupations of any given culture, generation or individual. If one knows how to interpret it, clothing can tell us so much about the period or occasion when it was worn, as well as about the men and women who designed and wore it. Besides, the beauty of historical dress – its colours, textures, shapes – is often astounding. I’m just as likely to be excited and inspired – moved, even – by a really beautiful evening gown by Paquin or Mainbocher as I am by a piece of Renaissance sculpture.

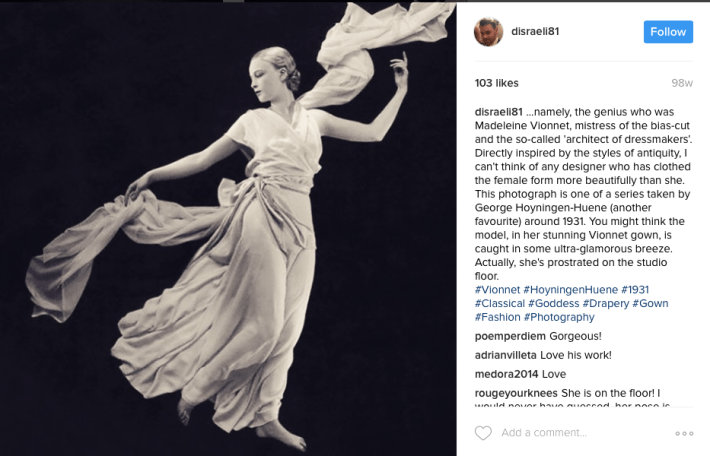

In your opinion, is fashion art? Absolutely. Great art is eternal; high fashion is, by its very nature, ephemeral. Yet the craftsmanship and virtuosity displayed by the finest garments – the exquisite embroidery on an eighteenth century silk waistcoat, say, or the complex construction of an evening gown by Madeleine Vionnet – are sufficient to transform them into timeless works of art as worthy of appreciation and close study as any painting or bronze. To me, fashion is art made to be worn. It’s that simple.

In your opinion, is fashion art? Absolutely. Great art is eternal; high fashion is, by its very nature, ephemeral. Yet the craftsmanship and virtuosity displayed by the finest garments – the exquisite embroidery on an eighteenth century silk waistcoat, say, or the complex construction of an evening gown by Madeleine Vionnet – are sufficient to transform them into timeless works of art as worthy of appreciation and close study as any painting or bronze. To me, fashion is art made to be worn. It’s that simple.

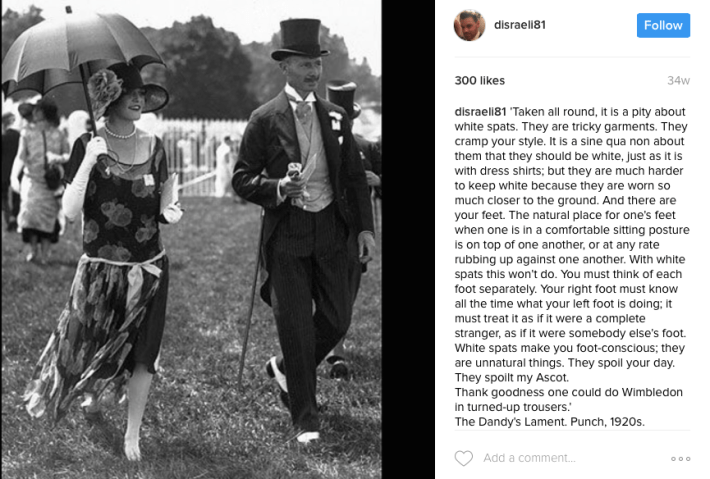

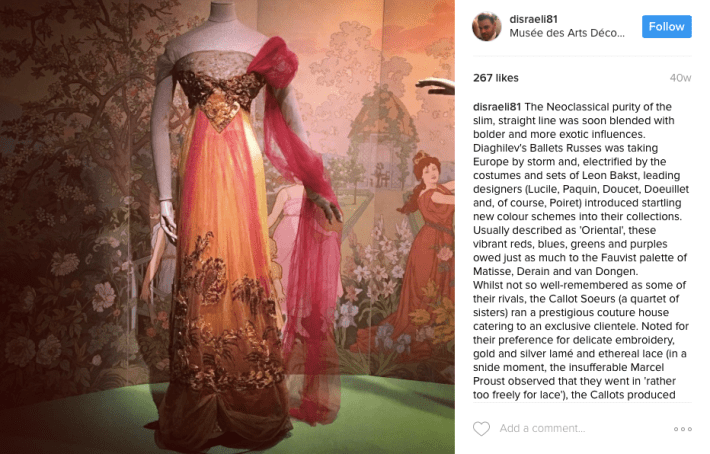

Favorite fashion designer, past and present: That’s a tough one! I’d have to start by listing the various decades or eras I’m particularly drawn to: the 1780s; the 1830s; the Roaring Twenties; the Glamorous Thirties; the New Look Fifties; the early Sixties. Lately, I’ve even surprised myself by developing an appreciation for Halston’s work from the 1970s – the decade often derided as the one that taste forgot! Most of all, I’m drawn like a moth to a flame to the Edwardian era, and particularly to that short window of time between 1910 and 1918. A former colleague once observed that, in the years immediately before the Great War, Western Europeans had, for the first time in history, an acute awareness of ‘the proximity of the future’. So much was changing so quickly. In society, politics, art and fashion, everything was in a state of upheaval and ferment: Votes for Women, Home Rule, the Russian Ballet, Post-Impressionism, motor cars, aeroplanes, telephones, wireless telegraphy…yet, for the privileged few, the opulent framework of a more leisurely and gracious age remained completely intact. You can see the conflicting currents of traditionalism and modernity collide to spectacular effect in the fashions of 1912, 1913 and 1914 – in my opinion, the most intriguing years in the entire history of dress. The long nineteenth century was coming to an end and the world as we know it today was being born.

In fashion, as in life, my tastes are fairly conservative. Like most people, I’m wowed by theatricalty and glamour. Deep down, however, I’m more attracted by the timeless principles of grace and classical elegance – yes, and femininity. In terms of favourite designers, I’d list the obvious: Lucile (who, in addition to her prodigious talent, had such a fascinating personal life); the Callot Soeurs (no other designers better understood colour and texture – and they trained Madeleine Vionnet); Christian Dior (who almost single-handedly revived the Paris couture industry after the Second World War); and Madeleine Vionnet herself (arguably the greatest designer ever). Increasingly, I find myself gravitating to designers who have yet to receive their fair share of coverage. Molyneux, Mainbocher and Augustabernard, all of whom were international fashion leaders between the wars, are figures I’d love to know more about – both personally and professionally.

In fashion, as in life, my tastes are fairly conservative. Like most people, I’m wowed by theatricalty and glamour. Deep down, however, I’m more attracted by the timeless principles of grace and classical elegance – yes, and femininity. In terms of favourite designers, I’d list the obvious: Lucile (who, in addition to her prodigious talent, had such a fascinating personal life); the Callot Soeurs (no other designers better understood colour and texture – and they trained Madeleine Vionnet); Christian Dior (who almost single-handedly revived the Paris couture industry after the Second World War); and Madeleine Vionnet herself (arguably the greatest designer ever). Increasingly, I find myself gravitating to designers who have yet to receive their fair share of coverage. Molyneux, Mainbocher and Augustabernard, all of whom were international fashion leaders between the wars, are figures I’d love to know more about – both personally and professionally.

If you could recommend one fashion or dress history related book to Art of Dress followers, what would it be? Again, I’m going to cheat: not one favourite book but three. First and foremost must be every fashion historian’s bible: Fashion: A History from the 18th to the 20th Century, written by Akiko Fukai and published by the Kyoto Costume Institute in Japan. A copy of this mighty tome (since released in two volumes) was presented to me by some friends when I was still at university. The incredible breadth and sheer quality of the Kyoto collection is extraordinary. And to see so many highlights exquisitely photographed in full colour is the next best thing to visiting the collection in person (that’s on my bucket list, by the way).

If you could recommend one fashion or dress history related book to Art of Dress followers, what would it be? Again, I’m going to cheat: not one favourite book but three. First and foremost must be every fashion historian’s bible: Fashion: A History from the 18th to the 20th Century, written by Akiko Fukai and published by the Kyoto Costume Institute in Japan. A copy of this mighty tome (since released in two volumes) was presented to me by some friends when I was still at university. The incredible breadth and sheer quality of the Kyoto collection is extraordinary. And to see so many highlights exquisitely photographed in full colour is the next best thing to visiting the collection in person (that’s on my bucket list, by the way).

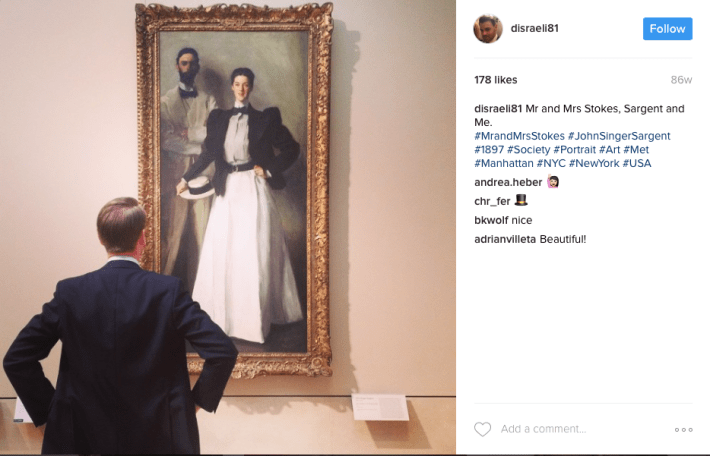

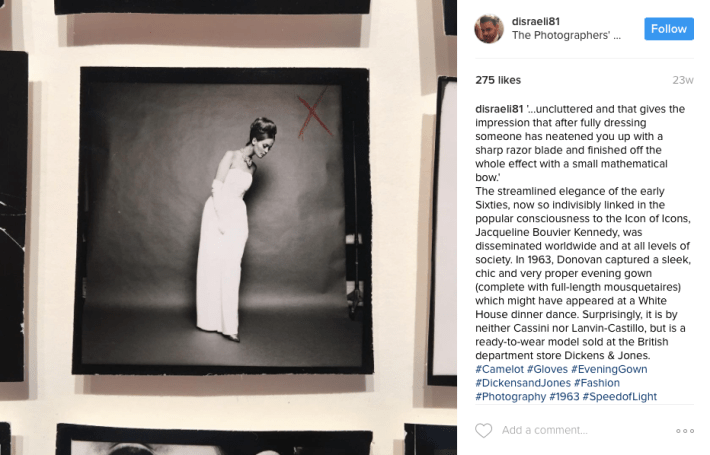

I’ve included a few more of my favorite @disraeli81 posts below:

*Charles Baudelaire, The Painter of Modern Life, (New York: Da Capo Press, 1964). Orig. published in Le Figaro, in 1863.

I love the command of fashion history knowledge in this post. As exquisite as the artist being featured. Kudos!

LikeLike

Reading Martin William’s interview was a pleasure and reminded me of two great men in London who would have passionately agreed that dress is “the best possible window into the social, political and cultural preoccupations of any given culture, generation or individual.” I am thinking of the great Geoffrey Squire (1925-2011), the former keeper and outstanding lecturer at the V&A who also had a connection to Sotheby’s, and one of the most inspirational teachers in the field, and the late Derek Shrub, the brilliant and charismatic director of the Sotheby’s Works of Art 10 month course. Those two men inspired me and countless others. It seems that Mr.Williams is carrying the torch at Sotheby’s.

LikeLike

A most enjoyable conversation with one of my favorite Instagram accounts. Thank you.

LikeLike