In this three part series, The Art of Dress will explore the influence of one of the world’s most beautiful birds, the peacock, and one of its “Golden” ages of influence on fashion from 1894-1920.

The brilliantly colored body and iridescent feathered train of the peacock—the male of the peafowl pavo species—has ensured its status as one of the world’s most beautiful birds. Immortalized in religion, myth, and folklore, peacocks from both species of the peafowl—the blue-bodied Indian and green-bodied Burmese—have proven to be sources of design inspiration in cultures the world over.

Appreciated for centuries in the West for its beauty, but also as a symbol of exotic luxury, the male peacock has long been a recurring motif in women’s fashionable dress. This series will celebrate the peacock in women’s fashion, jewelry, and costume during a period when it infiltrated all areas of artistic expression. This period straddling the dawn of the new century provided a ripe climate for exploring not only the aesthetic appeal of the sinuous and beautiful creature, but also the fascinating worlds from which it came.

The series will trace the peacock’s transition from a fashionable dress and accessory motif embraced by the Symbolist, Arts and Crafts, and Art Nouveau movements to its personification in the costumes of the greatest stars of the stage and screen during the 1910s.

Part One: Fashioning the Peacock

The peacock motif flourished in design during the end of the nineteenth-century, a time of heightened artistic expression in both Europe and America. After 1858, when Japan opened its doors to trade after years of isolation, images of the green peacock, depicted on various goods, came pouring into Europe. Responding to a lack of creativity in a growingly industrialized world, artists looked to sources, old and new, for inspiration. They embraced the green peacock found in Japanese imports but also the blue-bodied Indian peacock, and its white-bodied subspecies, as some one of their favorite subjects.

Private Collection. Image via Artstor.org.

During this period, women were often depicted alongside the colorful peacock or bejeweled in its iridescent feathers. In the image at left, the Symbolist painter Edgar Maxine employed the peacock in both a literal and a figurative sense. By depicting the peacock feather as a fashionable accessory, he is also alluding to the bird’s symbolic associations with pride and vanity. As the displaying peacock in the background demonstrates, the bird struts and shows off in an effort to find a mate. “Peacocking” was used to describe men, and occasionally women, who were observed to do the same.

The peacock provided adornment to feminine beauty that naturally translated into dress. Couturiers used the peacock motif in some of their most spectacular designs. Jewelers of the Art Nouveau and Arts and Crafts movements immortalized the peacock in a variety of metals and precious stones and “peacock blue” became a fashionable color in dress and interiors. As the Buffalo Tribune noted in 1905: “Hats, gowns, cloaks, jewelry, household decorations, are all being affected by the peacock fad.” The same article recognized that “when the peacock comes into fashion it gets into every phase of it.”

Below are featured six exquisite examples of the use of the peacock motif in fashion during this period.

The peacock inspired haute couture in the tea gown by the House of Worth featured here. Although tea gowns were worn for informal entertaining in the privacy of a lady’s home, they were no less luxurious than their evening gown couterparts. In this gown, the pattern of peacock feathers emphasizes the sheen of the lustrous silk satin.

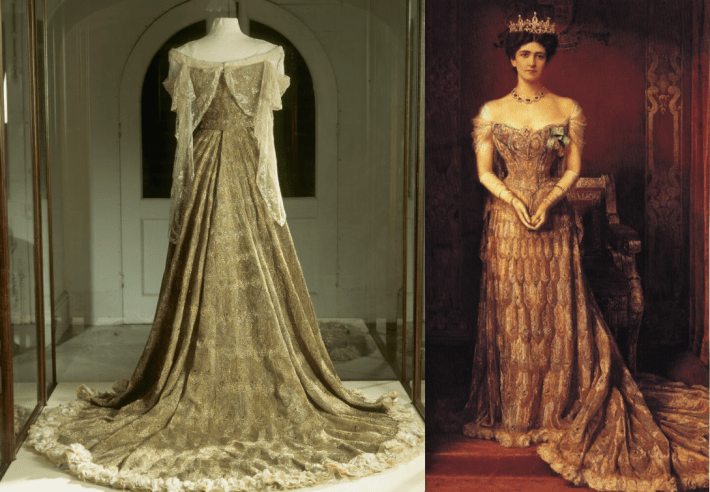

A signifier of royalty in India, the peacock feather proved a fitting motif for this elaborately embroidered dress worn in 1903 by Lady Curzon, the American-born wife of the British Viceroy to India. The dress was worn to the State Ball of Delhi Durbar at which King Edward VII was proclaimed Emperor of India. It was designed and made by the House of Worth but embroidered by skilled craftsmen in India. Iridescent beetle wings were used to dot the “eyes” of the silver and gold peacock feather motifs.

The Kyoto Costume Institute.

The green peafowl, or pavo muticus, is embroidered on this kimono by a leading Japanese export company. Originally from Burma (today’s Myanmar) in Central Asia, the green peacock found its way to Japan in the seventeenth century and became embedded in the country’s artistic traditions. In Japan, the peacock is a symbol of dignity and beauty; it is represented here alongside cherry blossoms, the eternal symbol for spring. In Europe and America, the Japanese kimono was especially fashionable as an informal at-home garment like the tea gown or dressing gown.

“I want to be a living work of art,” the eccentric Italian aristocrat the Marquise Luisa Casati, is portrayed in a flurry of broad brush strokes and peacock feathers. The Marquise often employed the peacock as an accessory to her avant-garde fashions as well as to the dramatic costumes she wore to her many famous masquerade balls. At one ball, she wore a diadem of peacock feathers dripping with fresh chicken blood. At another, she appeared as a golden goddess leading a peacock on a leash.

The Paris-based American designer Weeks makes the peacock itself—and not just its feathers—the center of attention on this dress. Embroidered on the bodice and screen-printed on the skirt, the peacock motif is highlighted against the streamlined silhouette of 1910. The peacock lent itself well to a new era in women’s fashion that embraced Asian influences.

The London store, Liberty & Company opened its doors in 1875 at a time of heightened Japonism in Europe, and at first was solely dedicated to selling Asian wares. The company eventually expanded to selling fabrics and fashions of its own design. Both the coat and cape employ Liberty’s “Hera” pattern. The peacock was an intimate friend of the Greek goddess, who placed the many eyes of her faithful servant Argus on its tail. “Hera” was one of Liberty’s most successful fabrics and is still associated with the company today.

Look for Part II next week!

Beautifully written and very inspiring. Thank you for sharing all these delightful insights to the fashion world!

LikeLike

Thank you, Pennie! I am so glad you are enjoying the site!

LikeLike